Until last year, I had never heard of John Bellairs. Upon reflection, this strikes me as somewhat odd: I have been reading fantasy since I was a child and Bellairs wrote fantasy for children almost exclusively. In fact, he was still writing up until his death in 1991, when I was five years old. It seems strange to me that I never encountered a single one of his books, but I can do little more at this point than shrug.

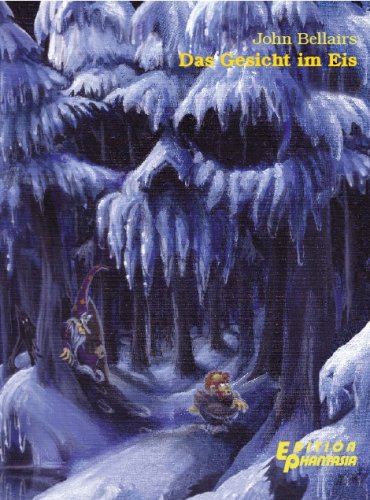

In any case, at some point last year I went to the movies and saw a trailer for a film based on one of his books, The House With A Clock In Its Walls. Something about the title intrigued me. I looked him up, and discovered he wrote a single novel for adults, published in 1969, called The Face In The Frost. Apart from the wonderfully alliterative title, covers from various editions boasted rave reviews from such fantasy stalwarts as Ursula K. Le Guin and Lin Carter. I sought it out immediately.

The Face In The Frost centers on two wizards, Prospero (“not the one you’re thinking of,” notes Bellairs) and Roger Bacon (who presumably is the one you’re thinking of). Both have been made uneasy by unusual phenomenon in recent months – odd noises, seeing things that aren’t there, and the like. Prospero thinks someone wants him dead. Roger suspects a connection with a mysterious book he has been tracking across England. After some investigating, they come to believe that the book has fallen into the hands of Melichus, an old rival of Prospero’s. Unfortunately, Melichus’ designs are not pleasant ones: an eternal winter begins to slowly envelop the world. Prospero and Roger set out to stop him.

What a delightful and unusual book this is! As I have noted before, many works of fantasy, particularly since the publication of J. R. R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings in 1954, have tried to conjure worlds that feel plausibly real. Bellairs has no such goal. He delights in the oddities that fantasy offers: singing mirrors, bubbling cauldrons, model ships that double as actual ships. His world doesn’t feel unreal, per se, but there is a quality to the writing that evokes fairy tales and storybooks.

The most unusual, and impressive, thing about it is how it is able to successfully shift tone on a dime. Much of the book maintains a light, if not outright comical affect; author Ellen Kushner described it as “the ‘Rocky & Bullwinkle’ of Fantasy.” And it is indeed a funny book; Bellairs pokes well-meaning fun at fantasy tropes throughout and I read much of it with a grin on my face. Yet, at times the story veers into wholesale horror, and these passages are nightmarish. Bellairs’ horror doesn’t depend on anything so easy as monsters, though he is happy to supply us with an appropriately hellish creature every once in a while. His horrors are more subtle: an unseen hand alighting on your shoulder, a face in the window, a child’s laughter drifting through the dark. Prospero’s night in an enchanted forest will haunt your dreams.

In researching the novel for this essay, I came across this quote from Bellairs regarding his intentions for the book:

“The Face In The Frost was an attempt to write in the Tolkien manner. I was much taken by The Lord of the Rings and wanted to do a modest work on those lines. In reading the latter book I was struck by the fact that Gandalf was not much of a person – just a good guy. So I gave Prospero, my wizard, most of my phobias and crotchets. It was simply meant as entertainment and any profundity will have to be read in.”

I was surprised to learn that Bellairs was so influenced by Tolkien, as I had prepared some remarks as to how The Face In The Frost is dissimilar from Tolkien in some major ways. For example, Bellairs does not devote nearly so much time to worldbuilding as Tolkien; the entire novel clocks in at under two-hundred pages. There is also the aforementioned sense of humor – The Lord of the Rings is overall a much more serious book. The Face In The Frost also acknowledges that it is set on Earth in a way that Tolkien’s work does not; though the book is set in the fictional North and South Kingdoms, Bellairs gives us references to England, Scotland, Wales, and other real geographical locations.

As you might expect from Bellairs’ comments above, it is the character of Prospero that really sets the book apart from its ilk. Most fantasy wizards tend to follow the model set by Gandalf: wise, knowledgable, and mysterious. While Gandalf does occasionally exhibit hints of an impish sense of humor, these are fleeting glimpses, and he certainly never submits to fear. Prospero, meanwhile, cracks jokes frequently, runs away from danger, and is afraid of ponies. He is a powerful wizard, but his foibles and fears make him feel more human than Gandalf ever did (although Gandalf was never really human anyway).

As much as I enjoyed the novel, I do have some criticisms. While the characters of Prospero and Roger Bacon are vividly drawn, the same cannot be said of the narrative or the villain. The central conceit is set up well, but we learn little of Melichus’ motives, personality, or history. I was particularly unsatisfied by the ending; after much talk of how Prospero is the only one who can stop Melichus, the dark wizard is ultimately defeated by a random character we meet only pages before the final showdown. Still, none of these criticisms were enough to sour my opinion of what is ultimately a very fine novel.

The Face In The Frost appears on Appendix N, Gary Gygax’s list of literary inspirations for Dungeons & Dragons. I do not feel that D&D owes as much to Bellairs as it does to someone like Jack Vance, but it is possible that Prospero’s practice of studying his spell books the night before he might need them influenced the game’s rule that magic users must do the same.

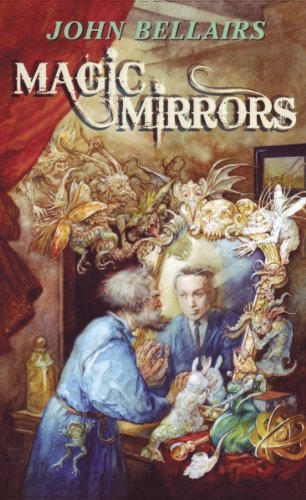

During the early 1980s, Bellairs began work on a sequel to The Face In The Frost called The Dolphin Cross, in which Prospero is kidnapped to a mysterious island. Unfortunately, Bellairs died before he could complete it; nonetheless, it eventually appeared in a 2009 anthology published by the New England Science Fiction Association called Magic Mirrors. A short story that describes how Prospero and Roger Bacon met is presumed lost.

In The Encyclopedia of Fantasy, John Clute describes The Face In The Frost as “a unique classic.” I agree. I have not read another fantasy novel that balances humor and horror so adroitly, nor one with such likably eccentric main characters. I think it’s a shame that the book isn’t better-known. If you see it the next time you’re browsing in your local bookshop, I recommend you pick it up.

NEXT TIME: A special announcement!