“You must save yourselves,” Rogol Domedonfors told them. “You have ignored the ancient wisdom, you have been too indolent to learn, you have sought easy complacence from religion, rather than facing manfully to the world.”

So intones the king before sinking into a five thousand-year slumber. His kingdom is technologically advanced but culturally stagnant. Its people have fallen into petty religious squabbles. He believes that if he removes the stability of his reign it will force his people to reconcile and grow. It does not. The kingdom devolves until two warring factions have grown so far apart that they literally cannot see each other. Then a stranger strides into their midst in search of treasure…

This is “Ulan Dhor,” the fifth of six stories that comprise Jack Vance’s The Dying Earth. But I get ahead of myself.

John Holbrook Vance was born on August 28, 1916. Weak eyesight prevented military service, but he was able to secure a position as a seaman in the Merchant Marine. Sailing proved to be a lifelong passion and is a motif in much of his work; in fact, he jointly built a houseboat with fellow science fiction authors Frank Herbert and Poul Anderson, which they then sailed in the Sacramento Delta. He was a devoted fan of Dixieland jazz, and played the cornet, ukelele, harmonica, and banjo.

He was also one of the most accomplished science fiction/fantasy authors of the 20th century. He won the Hugo Award three times (in 1963, 1967, and 2010), the Nebula Award, the Jupiter Award, the World Fantasy Award, and the Edgar Award (he wrote many mystery novels under the pseudonym Ellery Queen). In 1997 he was named the fourteenth Grand Master of the Science Fiction & Fantasy Writers of America, and in 2001 was inducted into the Science Fiction Hall of Fame. His work is characterized by carefully constructed prose that is frequently described as “baroque,” though I will touch on that later. He died in 2013 at the age of 96. He was a very prolific author: the Vance Integral Edition collects all of his writing into 45 hardback volumes.

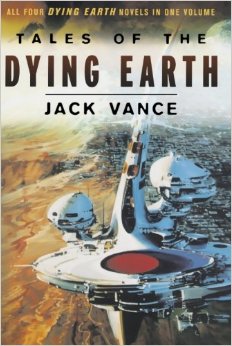

As you would expect given the age of this series, the individual volumes of the Dying Earth books are no longer available. They are, however, still in print in the Tales of the Dying Earth omnibus edition, published in 2000 by Orb Books (pictured above). This is the edition I bought, and while I have issues with the ridiculous sci-fi city pictured on the cover, the writing within is unimpeachable.

THE DYING EARTH (1950)

The Dying Earth is one of those legendary volumes that has had a lasting impact on future authors and other creative types, particularly within the sci-fi/fantasy field. It was ranked 16 out of 33 in Locus‘ 1987 poll of All-Time Best Fantasy Novels, and was one of five finalists for the 2001 “Retro Hugo” for Best Novel. It is what is termed a “fix-up,” that is, a novel comprised of short fiction that has been previously published. Oftentimes in fix-ups the author will edit the stories for consistency, or perhaps add a framing device to tie them all together.

Vance uses a different method, that of shared characters: A supporting character in one story will be the main character in another. The book opens on Turjan of Miir, a wizard who aims to create living beings using magic. He seeks the council of the seemingly omniscient Pandelume (who, like a creature from a H. P. Lovecraft story, brings madness to anyone who looks at him). Pandelume has created a beautiful woman named T’sais, but he created her incorrectly – she sees only ugliness, and hates the world and everyone in it. Turjan creates a girl named T’sain using his newfound knowledge. In the next story, Turjan is a prisoner, held by Mazirian the Magician, who aims to wrest from his captive the secret of creating life. In the next story, T’sais and T’sain meet, forcing T’sais to confront her bitter worldview. They also have a passing encounter with Liane the Wayfarer, a bandit who gets own story a few pages later.

These are not all the characters in the book, but I hope I have illustrated the organic way in which Vance weaves his stories together. There are plenty of other wonderful characters and creatures to be encountered here – Deodands, maneaters with skin black as night; Twk-Men, tiny men who ride dragonflies and offer information in exchange for gifts; Etarr, a witch who replaces her lover’s face with a demon’s; and perhaps my favorite, Chun the Unavoidable (the sobriquet is chillingly appropriate), who wears a cloak fashioned from the eyes of his victims.

I mentioned above that Vance’s writing is often characterized as “baroque,” which essentially means “mannered and ornately detailed.” Aspects of this I agree with – his writing is definitely mannered. I do not, however, think it is ornate, as that implies complicated sentence structures and advanced language. Vance’s writing doesn’t spin circles around itself. His sentence structures are quite accessible and tightly controlled. He will not use torrents of adjectives when one will suffice. While he does occasionally make use of what I call “dictionary vocabulary” (for example, “nuncupatory”), he most often opts for words that are unusual but can still be understood in context by the average reader. This is, I think, why his prose is such a joy to read: it doesn’t insult one’s intelligence, but it never becomes needlessly obtuse. Consider this excerpt from “Ulan Dhor”:

But even in my life I saw the leaching of spirit. A surfeit of honey cloys the tongue; a surfeit of wine addles the brain; so a surfeit of ease guts a man of strength. Light, warmth, food, water, were free to all men, and gained by a minimum of effort. So the people of Ampridatvir, released from toil, gave increasing attention to faddishness, perversity, and the occult.

This is wonderful writing, easily understood despite its seemingly complicated artifice.

I had expected to respect more than like this book. Friends who had read it informed me it does not reach the heights of later books in the series. While I agree with that assessment, I still loved this book. The writing is muscular and descriptive, the world enchanting. The characters, often anti-heroes, still find moments of humanity that are all the more touching because of their faults.

A brief note on the title: Vance’s preferred title for this book was Mazirian the Magician, and that is how it is titled in the Vance Integral Edition. The Dying Earth was chosen by Vance’s editor, and I honestly think it’s a much stronger, and certainly more evocative, title. Mazirian is not a major enough character, in my opinion, to warrant naming the entire book after him.

THE EYES OF THE OVERWORLD (1966)

“I categorically declare first my absolute innocence, second my lack of criminal intent, and third my effusive apologies.” – Cugel the Clever

After a sixteen year hiatus (so count your blessings, George R. R. Martin fans), Vance returned to the series with the second installment, The Eyes of the Overworld. Like the previous book, this is a fix-up, consisting of five novelettes originally published in The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction between December 1965 and July 1966, and one original chapter (“Cil”). Vance expanded and revised various portions of the different stories before publication of the book.

The plot centers on one of Vance’s most iconic creations: Cugel the Clever, an utterly amoral thief. He is persuaded by a wealthy merchant to rob the home of a nearby magician, who catches Cugel in the act. As recompense, Cugel agrees to retrieve a special item for the magician – a violet contact lens which, when worn, shows the wearer the Overworld, an improved version of reality where a hut becomes a palace, a table scrap becomes a feast, and the ugly become beautiful. To ensure Cugel’s compliance, the magician affixes a barbed and hooked alien named Firx around Cugel’s liver. Then he dumps Cugel in the northern wastelands, leaving the particulars of obtaining the Eye and returning home to the thief.

Vance’s preferred title for this book was Cugel the Clever, and that is how it is titled in the Vance Integral Edition. I think this is a more fitting, if less interesting, title than The Eyes of the Overworld, as the Eyes themselves only really feature in the early section of the book. This is in form a classic picaresque novel; character is ultimately more important than story, and the story itself is episodic rather than cohesive.

Still, what a rich set of episodes! My favorite, I think, finds Cugel arriving at a village after long and exhausting travel. The mayor offers him a job that will pay him the entirety of the town’s savings, a prospect the greedy Cugel cannot resist. The job itself seems simple: He must sit atop a tall pole and watch for Magnatz, the mythical enemy of the village. But Cugel is deceived; once he has taken his place at the top of the watchtower he is stranded. The townsfolk provide food with a system of ropes and pulleys, but will not let him down. Cugel decides to escape. The consequences are exciting and unexpected. Another memorable adventure sends Cugel back in time one million years. This is a terrifically entertaining book, more interesting and fulfilling than The Dying Earth.

Cugel himself is a classic Vancian anti-hero. He is a liar, a cheat, a rapist, a killer, a coward, and a thief, yet considers himself superior to everyone around him. He is a wholly unlikeable character, and yet by the end of the story Vance has managed to evoke a surprising amount of sympathy for him, which he accomplishes by fashioning most of the other characters to be even less likable than Cugel is. For every con Cugel successfully pulls off, he is conned himself twice over. In many ways, “the Clever” is an ironic title, and this contradiction is a source of much of the novel’s humor. Cugel’s final blunder at the end of the book is the ultimate expression of his incompetence.

Another seventeen years would pass before Vance returned to the Dying Earth. Cugel’s Saga, a direct sequel to The Eyes of the Overworld and twice as long, appeared in 1983. In the interim, Michael Shea (Nifft the Lean) wrote an authorized sequel called A Quest for Simbilis, which was published in 1974.

Apart from the aforementioned Cugel’s Saga, there is one more book in the series, called Rhialto the Marvellous. These two books shall be covered in a separate post. For the rest of this post, I would like to cover a less obvious topic: Vance’s influence on roleplaying games.

One cannot have a discussion of Vance’s series without acknowledging its impact on a certain game known as Dungeons & Dragons. Both The Dying Earth and The Eyes of the Overworld are included in the famous Appendix N, a list of literary works that influenced D&D creator Gary Gygax (read it here). Many of the listed authors influenced setting and tone more than anything else, but a few of them – such as Vance – had a direct impact on the mechanics of the game. Indeed, Vance is one of the few authors Gygax specifically singles out for his contribution (he even wrote an essay praising his hero, “Jack Vance and The D&D Game,” which you can read here). While Cugel the Clever is an obvious template for the Thief character class, the more important influence was on how magic worked in the game.

In Vance’s stories, magic-users must memorize spells before they can use them. The spells are so complicated, and take up so much mental space, that the user forgets them the instant they are cast. Moreover, their sheer complexity limits how many one can remember at a time. Mazirian the Magician, for example, “by dint of stringent exercise, could encompass four of the most formidable, or six of the lesser spells.” Thus, choosing exactly which spells to use, and when to use them, becomes of utmost importance. Vance uses this device to generate suspense: As his characters gradually run out of spells, with no opportunity to memorize new ones, their situations become more and more dangerous. This system is known as “Vancian magic” in the gaming community, and while later editions of D&D changed how magic worked, this was the norm for many years. In addition, spells and items mentioned in the novels, such as Prismatic Spray and Ioun stones, made their way into the game, and the name of the magic diety Vecna is an anagram of Vance.

Vance’s influence is not limited to just D&D. Another roleplaying game called Talislanta, written by Stephan Michael Sechi and intentioned as a simpler alternative to D&D, owes so much to Vance that every edition of the game has been dedicated to him. In 2001 Pelgrane Press released The Dying Earth Roleplaying Game, a direct adaptation of Vance’s novels, written by author and game designer Robin Laws.

As I said above, the last two books of the Dying Earth series will be covered in a future post, which will also contain a discussion of Vance’s influence on future authors. Until then, the next few entries here will cover short stories, as I can get through them at a faster pace than novels. In the meantime, I highly recommend everyone read The Dying Earth and The Eyes of the Overworld. I loved them both. They more than earn their status as classics.

NEXT TIME: “Aye, and Gomorrah…” by Samuel R. Delany!