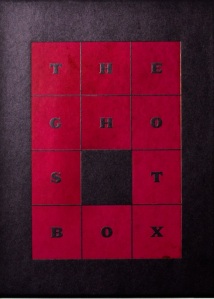

This is the first entry in a month-long series focusing on a horror anthology edited by Patton Oswalt called The Ghost Box (buy it here). The blog will resume its standard format in November.

* * *

Not much is known about Henry Ferris Arnold. He was born in Galesburg, Illinois in 1902 and graduated from Knox College in 1923, serving as a 1st Lieutenant in the U.S. Army during World War II. He married a woman named Margaret Ives, but the marriage ended in divorce. He died in Orange County, California in 1963 at the age of 61. From 1926 to 1937, Arnold published three stories in the magazine Weird Tales, and these constitute the entirety of his published fiction.

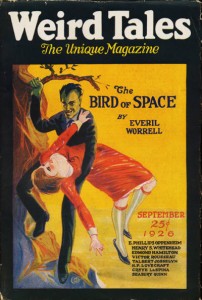

The first was called “The Night Wire,” and appeared in the September 1926 issue. It ended up being one of the most popular stories the magazine published during the period – so popular, in fact, that it was reprinted in the January 1933 issue. Read it here.

“The Night Wire” is about a man who works the night shift at a telegraph office. His job, and that of his single co-worker, is to monitor and transcribe the messages that come in over the wire. His co-worker, John Morgan, is so skilled that he can transcribe from two machines simultaneously. There’s usually no need for that, though; the news is slow while the world sleeps.

Tonight, however, Mr. Morgan’s skills are needed. Strange messages start to come in over the wire. It would seem that in a town called Xebico – the narrator has never heard of such a place – a strange fog has appeared from nowhere. It hangs over the town, growing ever more dense. Screams are heard from within. Those who enter the fog to investigate never return. Strange lights appear in the sky. Inhuman figures are seen in the mist. There are reports of townspeople being “consumed – piecemeal.” Whatever is going on, it is unprecedented and apocalyptic.

Up until the ending, “The Night Wire” is an astonishing bit of storytelling. A good deal of its power comes from its economy. Telegraphs, when they were still in operation, were all about brevity, squeezing the most detail into the fewest number of words. This scheme is reflected in Arnold’s prose. The story is no more than five or six pages, and every paragraph is essential, every detail precisely chosen. This is contrasted with the actual telegraphs the narrator reads in the story – while the initial dispatches from Xebico are terse and mysterious, as the story proceeds they grow ever longer and more elaborate, until entire paragraphs are coming over the wire.

Arnold’s decision to separate his narrator from the action is a stroke of genius. It is a terrific method for generating suspense: like the narrator, we are helpless, waiting breathlessly for updates from the wire. Orson Welles would use the same device to similar effect twelve years later in his 1938 radio broadcast of H. G. Wells’ The War of the Worlds. The mood that is conjured by all of this is extraordinary – Arnold convincingly evokes the panic, confusion, fear, and horror that accompanies a sudden attack by an unknown foe, maintaining an atmosphere of dread that is the hallmark of the best weird fiction (in their anthology The Weird, Anne and Jeff VanderMeer praise the story as “a perfect example of how weird creates not just unease, but dislocation”).

Now, onto that ending. After reading the last update from Xebico, the narrator discovers that Morgan has been dead for hours, apparently typing his dispatches from beyond the grave. A subsequent search of a world atlas reveals no town called Xebico. Was Morgan tapping into broadcasts from another reality? Did the fog travel through the wire and kill Morgan? Was it all just the fever dream of a dying man? Arnold steadfastly refuses to say.

This, to me, presents something of a problem. On the one hand, I respect Arnold’s instinct to keep his mysteries hidden. It is commonly accepted that what you don’t see is scarier than what you do. In that sense, the ending – with all its troubling implications – is effective. On the other hand, I think the actual twist is a cheap one, the equivalent of the writer shouting “boo!” at the reader. There are other endings that would have cohered more strongly with what came before. If I had written it, it would have ended with the narrator looking out the window to see the fog has reached him too (a twist that is even suggested by Arnold at one point).

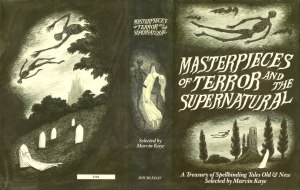

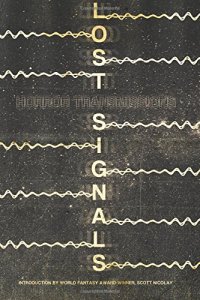

Despite its middling ending, “The Night Wire” is easily recommended, a wonderful example of the weird tale well worth reading even in the age of cell phones and social media. Horror fans reading it today are sure to draw comparisons to John Carpenter’s film The Fog, as well as Stephen King’s novella “The Mist” (both from 1980), though “The Night Wire” has more in common with Carpenter’s work than King’s. It’s been reprinted in many anthologies over the years, such as the 1985 collection Masterpieces of Terror & The Supernatural, with its wonderful cover by Edward Gorey, and the more recent Lost Signals: Horror Transmissions (2016). Its inclusion in The Ghost Box helps to ensure that it will continue to be read for a long time.

NEXT TIME: “The Late Shift” by Dennis Etchison!