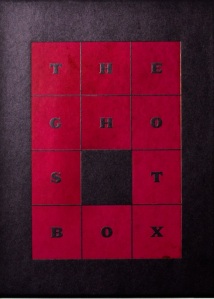

This is the eleventh and final entry in a month-long series focusing on a horror anthology edited by Patton Oswalt called The Ghost Box (buy it here). The blog will resume its standard format in November.

* * *

Chelsea Quinn Yarbro was born in Berkeley, California in 1942. She is the author of over seventy novels in a variety of genres, but she is best known for a series of historical horror novels following the adventures of the vampire Count Saint-Germain (there are to date twenty-eight novels in the main series, with several additional spin-off novels). Science-fiction fans may appreciate that Yarbro played a key role in popularizing The Eye of Argon, a legendarily bad fantasy novella that is read aloud at conventions as a game (the goal of the game is not to laugh while reading; if you lose, you stop reading and pass it on to the next person). In 2009, Yarbro was awarded the Bram Stoker Award for Lifetime Achievement. She is also a cartographer, multi-instrumentalist, and composer.

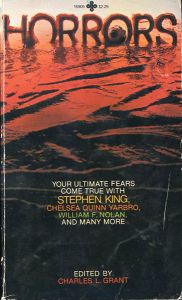

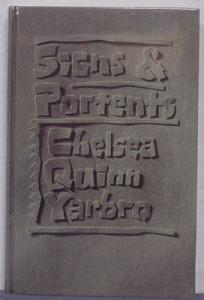

“Savory, Sage, Rosemary, and Thyme” was first published in a 1981 anthology edited by Charles L. Grant called Horrors, which also contains another story in The Ghost Box, “Shadetree” by Michael Reaves (reviewed here). It can also be found in Yarbro’s 1984 short story collection Signs & Portents.

“Savory, Sage, Rosemary, and Thyme” is the story of Amy Macklin (making this is the second story in The Ghost Box with a main character named Macklin), a teenage girl who has just fallen in love for the first time. The boy she loves, however, only has eyes for someone else. There is a woman who lives up a nearby mountain, called the Herb Woman. People laugh at her remedies and potions and folk magic, but Amy thinks she might find aid there. She trundles up the mountain in the dead of night to consult with the Herb Woman. She doesn’t get the help she asks for, but she does get the help she needs.

There are similarities between this story and “Shadetree,” though of course they could not have been intentional. Both stories are set in small, conservative Southern towns. Both feature strong-willed, intelligent women as main characters. Both feature elderly people who are repositories of ancient and magical knowledge, and in both stories the main characters are aided by that knowledge to defy society’s expectations of them. If the plot of “Shadetree” is arguably stronger than “SSR&T,” the latter has an advantage in that its writer is a woman.

The men in this story are not intentionally evil, but they are most certainly products of a patriarchal society. Amy’s father polices her body with an almost sinister sort of jealousy, while her crush sees women as little more than sexual conquests. Her teacher, noticing her unusual intelligence, wants to steer her onto the path of academia: a well-meaning plan, to be sure, but he is still deciding what is best for her on his own. This is a story about a girl who, with the aid of other women, learns about men and finds power within herself to fight against the suffocating forces of the patriarchy.

A 1984 review of Signs & Portents in The Washington Post describes the story’s ending as “hasty,” and I must agree. It’s not a bad ending – what must happen does – but it happens in the span of a few pages, while the rest of the story is much more relaxed. It’s hard not to feel that Yarbro was ready to be done and move on to something else. That’s a minor complaint, though. I ultimately wound up finding “SSR&T” to be one of the strongest stories in the collection.

* * *

BONUS MINI-ENTRY: “Hallowe’en In A Suburb” by H. P. Lovecraft

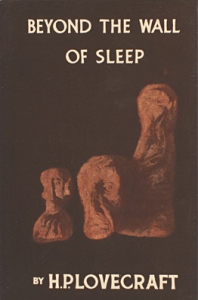

The Ghost Box closes out with a poem by H. P. Lovecraft called “Hallowe’en In A Suburb.” The poem is not printed in a chapbook like the stories; rather, it is printed on the bottom of the inside of the box, only visible once it is empty. The poem first appeared in The National Amateur in March of 1926, and was first collected in a 1943 Arkham House edition of Lovecraft’s work called Beyond the Wall of Sleep. Read it here.

This is a short poem, only seven stanzas long. Each stanza follows a rather unusual ABCBB rhyme scheme. It does not tell a story, but rather attempts to evoke the macabre atmosphere and excitement of Halloween. There is surprisingly little commentary on suburban life, but much talk of vampires, ghouls, witches, and other things that go bump in the night. The tone of the poem is light throughout; Lovecraft does not aim to frighten here. Indeed, the poem seems fueled by childhood nostalgia. Short and sweet, it’s a perfect grace note to wrap up the collection.

* * *

All in all, I’ve greatly enjoyed reading The Ghost Box. Some stories were stronger than others, but that’s to be expected with any short story collection. A few of them, such as “Pumpkin Head” and “The Clock,” made an indelible impression on me and I consider them new favorites. Hingston & Olsen released a second Ghost Box this year, also edited by Mr. Oswalt, and I intend to review that collection in its entirety next April. Why April? Simple: if I know Patton (and I don’t, but bear with me), a Ghost Box III is likely to be released next October, and I want to to be able to review it freshly published.

I hope you all have enjoyed the last month’s reviews. As this month was dedicated to horror stories, the next few months will focus more heavily on science-fiction and fantasy. I hope you’ll join me.

NEXT TIME: “Bloodchild” by Octavia Butler!