I don’t believe it’s unreasonable to say that there are two major periods of 20th century fantasy: the period before The Lord of the Rings, and the period after. No other work of fantasy has achieved the cultural impact of J. R. R. Tolkien’s 1954 epic. Before Tolkien, fantasy was just that. Characters had silly-sounding names that weren’t tied to a culture or history; they just needed to sound “fantasy-like.” A professor of literature and languages at Oxford, Tolkien wanted his stories to seem real. He invented entire languages and histories, creating worlds that felt more authentic than any that had come before. A small army of authors have tried, with varying degrees of success, to mimic Tolkien’s strategy. And then there are those who have deliberately rebelled against it.

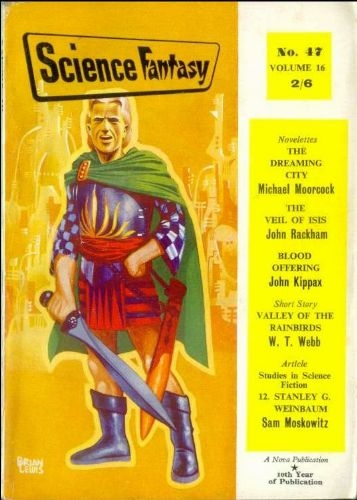

One such author was Michael Moorcock. Born in London in 1939, Moorcock started writing while he was still in school. He served as editor of the science-fiction magazine New Worlds from 1964-1971, and then again from 1976-1996. Much of his fiction, which he has been publishing since the 1950s, revolves around a figure known as the Eternal Champion, a hero who exists across all dimensions and maintains the cosmic balance. “The Dreaming City,” first published in the June 1961 issue of Science Fantasy, features the first appearance of perhaps the most famous incarnation of the Eternal Champion: Elric of Melniboné.

The Elric stories are set on Earth, sometime before or after (Moorcock lets you take your pick) the great human civilizations have risen and fallen. For ten thousand years of this nebulous history, the kingdom of Melniboné stood supreme. Elric is the last king of this once-great empire, long since fallen by the time “The Dreaming City” begins. The story concerns Elric’s quest to sack the last standing Melnibonéan city and rescue his lost love from the clutches of his evil cousin Yyrkoon, who has usurped the throne.

Moorcock’s agenda is fully formed from the beginning. Everything about this story seems calculated to upend what we expect in post-Tolkien fantasy fiction. Unlike Tolkien’s work, described by M. John Harrison as “stability and comfort and safe catharsis,” Moorcock’s vision is dark and chaotic. To me, it seems to blend the work of Robert E. Howard, H. P. Lovecraft, and Edgar Rice Burroughs into one while subverting the clichés of each, and the result is potent. There is no black-and-white morality here. The Melinibonéans at first evoke the wizened elves of Tolkien, but we quickly learn they were a cruel and callous race of sorcerers who obtained their formidable magics by making pacts with demons.

Elric himself is about as far from your standard-issue fantasy hero as you could ask for. Consider a character like Conan, or Aragorn from The Lord of the Rings. These are physically imposing, taciturn but morally righteous characters. They are archetypal heroes. You know they will be victorious in their struggles because they are strong and virtuous and combat forces of obvious evil.

Elric, meanwhile, is weak and frail. He could be described as handsome, but his red eyes unsettle all those around him. He requires a steady supply of herbal drugs just to stay alive. Unlike Conan, he is no master with a sword. In fact, his sword is the master of him: the blade he carries, Stormbringer, is sentient and behaves with a mind of its own on the battlefield. Elric is dependent on Stormbringer for his victories – a dangerous bargain, since Stormbringer eats souls. Elric has a conscience, but it is a weary one, and he will often act out of revenge or anger.

Fantasy anti-heroes are nothing new today, but I can scarcely imagine how bracing this story must have felt in 1961, with its brooding protagonist and morally grey universe. Reading it today, I found it an obvious precursor to the sub-genre known as “grimdark,” dystopian fantasy that is dark, bloody, and rejects simplistic moralizing (an excellent point of reference in the modern era is George R. R. Martin’s A Song of Ice and Fire). It’s hard to imagine a figure like Karl Edward Wagner’s Kane existing without Elric.

And speaking of blood, boy is “The Dreaming City” bloody! This is one of the most violent fantasy stories I have read in some time. People are burned to death, impaled, shot with arrows, chopped in half, have their faces cut off, drown, and endure all sorts of other nasty things I have not yet mentioned here. To be honest, it felt a little much to me at times, though I imagine Moorcock intended it as a counterpoint to Tolkien’s somewhat sterile military battles.

Moorcock once described himself as “a bad writer with big ideas.” I do not concur with this assessment. He is not as skilled a stylist as M. John Harrison or George R. R. Martin or Gene Wolfe, but his prose captures the flavor and excitement of Robert E. Howard with none of the excess verbiage. I particularly like his description of the Dreaming City itself:

“Built to follow the shape of the ground, the city had an organic appearance, with winding lanes spiraling to the crest of the hill where stood the castle, tall and proud and many-spired, the final, crowning masterpiece of the ancient, forgotten artist who had built it. But there was no life-sound emanating from Imrryr the Beautiful, only a sense of soporific desolation. The city slept – and the Dragon Masters and their ladies and their special slaves dreamed drug-induced dreams of grandeur and incredible horror, learning unusable skills, while the rest of the population, ordered by curfew, tossed on straw-strewn stone and tried not to dream at all.”

“The Dreaming City” was first collected in a 1963 volume called The Stealer of Souls, which was later repurposed as part of “the third novel of Elric of Melniboné,” The Weird of the White Wolf. I read it in an omnibus called Elric: The Stealer of Souls. No matter where you read it, it is worth seeking out, as are the rest of the Elric stories. The setting is fascinating, the action compelling, and the leading man (and his sword) unforgettable. I very much enjoyed it. If you are a fantasy fan, consider this essential.

NEXT TIME: THE FACE IN THE FROST by John Bellairs!