The Golden Age of Science Fiction is generally agreed to have begun in 1939 and ended, depending on who you ask, as early as 1946 or as late as 1960. It came after the pulp era of the 1920s and ’30s, and before the experimental New Wave sci-fi of the ’60s and beyond. Many of the genre’s most famous authors – among them Isaac Asimov, Robert A. Heinlein, Ray Bradbury, and Arthur C. Clarke – made their names during this period. Golden Age sci-fi strikes a particular tone, favoring scientific accuracy, adventurous settings, linear narratives, and heroes (overwhelmingly male) who solve problems with can-do spirit.

I have already said that the Golden Age of Science Fiction began in 1939, but more specifically, it began with the July issue of Astounding SF. John W. Campbell had taken over as editor two years earlier, and the magazine had been improving in quality with each issue (Golden Age sci-fi is sometimes called “Campbellian science fiction,” as Campbell’s influence dominated the field for years). This was one of the first truly great issues under his leadership. It included the first story by Isaac Asimov to appear within its pages, but the real groundbreaker was the tale featured on the cover: “Black Destroyer,” by the Canadian writer Alfred Elton van Vogt (read it here).

The plot is simple enough. Intrepid explorers land on an alien planet to investigate the ruins of an ancient city. They think they are alone. They are not. They are stalked by the Coeurl, a large cat-like creature. The Coeurl has exhausted its food supply, and in the humans it sees a chance for survival. It allows itself to be taken aboard their ship, where it begins to kill the crew and build a ship of its own in an attempt to escape to the freedom of space.

It’s not hard to see why sci-fi scholars point to this specific story as the start of the Golden Age of Science Fiction. The literary qualities I described at the beginning of this essay are fully formed here. Adventurous setting: check. Linear narrative: check. Plucky human heroes: check. Scientific accuracy: well, I suspect van Vogt didn’t consult any scientists before writing this, but he at least attempts to make his science seem plausible. Reading this story today, you recognize a template for a great deal of the popular sci-fi that followed, particularly the 1956 film Forbidden Planet and, on television, the original incarnation of Gene Roddenberry’s Star Trek (1966-69).

Historical importance aside, though, the quality of van Vogt’s prose is wildly uneven. Many of his sentences are laughable – one paragraph begins, “The little red sun was a crimson ball” – but others achieve a weird power. The opening paragraphs are as good a demonstration of his style as any.

“On and on Coeurl prowled! The black, moonless, almost starless night yielded reluctantly before a grim reddish dawn that crept up from his left. A vague, dull light it was, that gave no sense of approaching warmth, no comfort, nothing but a cold, diffuse lightness, slowly revealing a nightmare landscape.

Black, jagged rock and black, unliving plain took form around him, as a pale-red sun peered at last above the grotesque horizon. It was then Coeurl recognized suddenly that he was on familiar ground.”

Ugh. That is bad. “Nightmare landscape”? “Unliving plain”? “Grotesque horizon”? I don’t even know where to begin with that description of light. The story is full of such language. Still, despite its clumsiness, there’s something evocative about it. Van Vogt has a vision, and that vision is compelling; it is simply that he is not quite able to express it with the poetry it deserves. He gets just close enough that we keep reading.

Stephen King is less generous than I am in his assessment of van Vogt’s abilities. In a 2013 article for The Atlantic, King opined that “he was just a terrible, terrible writer. His short story, ‘Black Destroyer,’ begins: ‘On and on, Coeurl prowled!’ You read that, and you think – my god! Can I really put up with even five more pages of this? It’s just panting!”

King is not the first to make such comments. An early critic of van Vogt’s was Damon Knight (author of, among other things, “To Serve Man,” the basis of a celebrated episode of The Twilight Zone). Knight wrote, “In general van Vogt seems to me to fail consistently as a writer in three elementary ways: 1. His plots do not bear examination. 2. His choice of words and sentence-structure are fumbling and insensitive. 3. He is unable to either visualize a scene or to make a character seem real.”

Knight’s observations have merit. Van Vogt’s writing, as previously discussed, stumbles often. As for characterization, I will say that the Coeurl is a vividly imagined creature. We get a good sense of its history, motivations, and capabilities. The humans, though, are boring, barely defined archetypes. We get names, job titles, and little else. I didn’t mind at all when any of them met a horrible demise. To be honest, by the end I was rooting for the creature. Considering how the story concludes, that’s a disappointment.

Not everyone agreed with Knight’s assessments, though. One of van Vogt’s stalwart defenders was Philip K. Dick, who wrote, “There was in van Vogt’s writing a mysterious quality…all the ingredients did not make a coherency. Now some people are put off by that. They think it’s sloppy and wrong, but the thing that fascinated me so much was that this resembled reality more than anybody else’s writing inside or outside science fiction.” Harlan Ellison wrote, “Van was the first writer to shine light on the unrestricted ways in which I had been taught to view the universe and the human condition.”

While the story that spawned it has been more or less forgotten except by genre aficionados, the Coeurl lives on in popular culture. It was the inspiration for the displacer beast, a classic monster in the tabletop role-playing game Dungeons & Dragons, and has appeared as an enemy in the Final Fantasy video game series since 1988. I would also argue that the Coeurl inspired the “salt vampire,” which drains sodium from its victims, in the 1966 Star Trek episode “The Man Trap.”

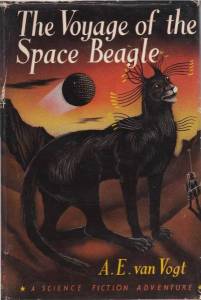

In 1950, van Vogt reworked “Black Destroyer” into the first section of his fix-up novel The Voyage of the Space Beagle (the term “fix-up” was coined by van Vogt himself). One of the other stories integrated into the novel was called “Discord in Scarlet,” originally published in the May 1950 issue of Other Worlds. The first story describes a nearly indestructible alien creature killing the crew of a human spaceship off one by one. The second describes an alien stowaway that implants parasitic eggs in the stomachs of the ship’s crewman. If you think this sounds like Ridley Scott’s 1979 film Alien, you will not be surprised to learn that van Vogt thought so too. He sued 20th Century Fox for plagiarism, but the case was settled out of court.

To conclude, I don’t know if I’d recommend this to the casual reader. At this point there are far better “evil alien stalks human prey” stories to choose from; as I’ve already discussed, there are significant issues here with characterization and quality of writing. If you’re interested in the history of science fiction, though, this is an essential read.

NEXT TIME: ANNIHILATION by Jeff VanderMeer!